Zero, zilch, nothing, is a pretty hard concept to understand. Children generally can’t grasp it until kindergarten. And it’s a concept that may not be innate but rather learned through culture and education. Throughout human history, civilizations have had varying representations for it (the ancient Romans, for instance, had no numeral for zero, but the ancient Mayans did).

Yet our closest animal relative, the chimpanzee, can understand it. And now researchers in Australia writing in the journal Science say the humble honey bee can be taught to understand that zero is less than one.

The result is kind of astounding, considering how tiny bee brains are. Humans have around 100 billion neurons. The bee brain? Fewer than 1 million.

The findings suggest that the ability to fathom zero may be more widespread than previously thought in the animal kingdom — something that evolved long ago and in more branches of life.

It’s also possible that in deconstructing how the bees compute numbers, we could make better, more efficient computers one day.

Our computers are electricity-guzzling machines. The bee, however, “is doing fairly high-level cognitive tasks with a tiny drop of nectar,” says Adrian Dyer, a Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology researcher and co-author on the study. “Their brains are probably processing information in a very clever [i.e., efficient] way.”

But before we can deconstruct the bee brain, we need to know that it can do the complex math in the first place.

How to teach a bee the concept of zero

Bees are fantastic learners. They spend hours foraging for nectar in among flowers, can remember where the juiciest flowers are, and even have a form of communication (called a waggle dance) to inform their hive mates of where food is to be found.

Researchers train bees like they train many animals: with food. “You have a drop of sucrose associated with a color or a shape, and they will learn to reliably go back to” that color or shape, Dyer explains.

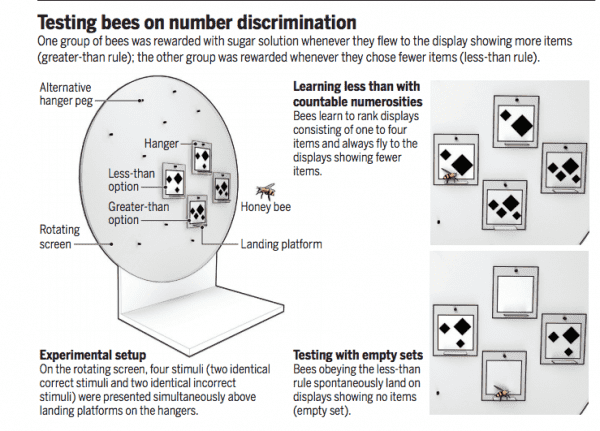

With this simple process, you can start teaching bees rules. In this case, the researchers wanted to teach 10 bees the basic rules of arithmetic.

So they put out a series of sheets of paper that had differing numbers of objects printed on them. Using sugar as a reward, the researchers taught the bees to always fly to the sheet that had the fewest objects printed on it.

Once the bees learned this rule, they could reliably figure out that two shapes are less than four shapes, that one shape is smaller than three. And they’d keep doing this even when a sugary reward was not waiting for them.

And then came the challenge: What happens when a sheet with no objects at all was presented to the bees? Would they understand that a blank sheet — which represented the concept of zero in this experiment — was less than three, less than one?

To a degree much greater than chance, they did, and chose the blank page 60 to 70 percent of the time. And they were significantly better at discriminating a large number, like six, from zero, than they were in discriminating one from zero. That finding “is actually consistent with the idea that zero is a hard thing for the brain to represent,” Dyer says.

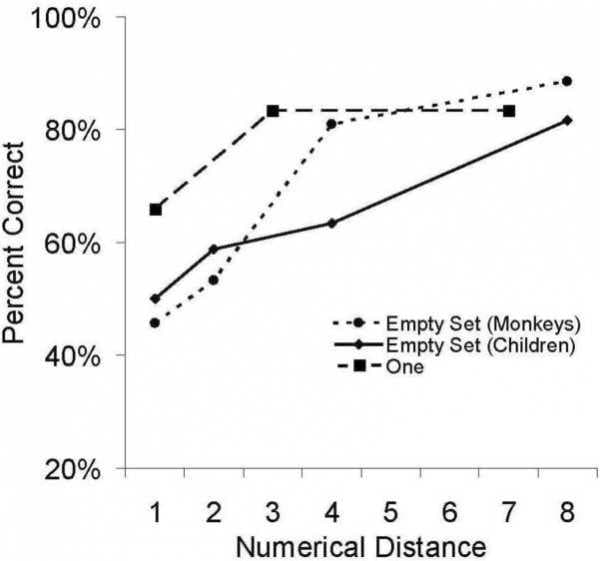

It’s actually a pattern also seen in experiments with young children and monkeys. The following chart is from a study on 4-year-old humans’ ability to pick a card with the smallest number of objects represented on it (much like the task the bees accomplished).

The chart compares the kids’ performances to a similar study conducted on monkeys. When a card with zero objects on it (the “empty set”) was presented alongside cards with many objects, both the children and the monkeys performed well on the task. When the empty set was shown alongside a card with only one object on it, all the primates had a much harder time.

The bee researchers also ran a number of control experiments, ruling out, among other things, that the bees simply preferred to fly near a blank sheet of paper. “It took about three years to collect all the control experiments to prove that it was a genuine representation of the concept of zero,” Dyer says.

Bees are incredible thinkers

In previous work, Dyer and his team have shown bees are capable of an amazingly complex array of tasks. For instance, he and his colleagues found in 2010 that bees can be trained to learn and remember human faces, and they do it in a manner that’s not entirely different from the way we do it.

In a supplement commentary in Science, Andreas Nieder, a German neurobiologist, explains why it’s so astonishing that humans and bees demonstrate similar cognitive abilities.

“Their last common ancestor, a humble creature that barely had a brain at all, lived more than 600 million years ago, an eternity in evolutionary terms,” Nieder writes. But somehow, separately, both vertebrates and insects developed these similar skills.

Related

20 photos of bees that will make you say “damn, bees are beautiful”

It’s possible that bees are just oddly smart compared to other insects, but Dyer suspects his results suggest “probably a much broader spectrum of animals can process” the idea of zero. Though it would take individually training and testing different species of animals to prove this hunch. Scientists don’t even understand the human brain’s comprehension of nothingness all that well.

In the meantime, we can marvel at the ingenuity of bees — and consider what we’ll lose if bee colony collapse disorder continues to devastate these remarkable creatures.

Learning how their tiny brains work helps us appreciate the power of our own.

“What is nothing?” Dyer explains, is a question that “seems a bit simple to us. But the actual ability to do it took a long time to arrive in human culture. And so it’s not straightforward, so understanding how a brain [a bee brain, a human brain, etc.] does it is exciting.”

Sourse: vox.com