Toto Wolff has admitted he would not blame Lewis Hamilton for seeking a move away from Mercedes if the sport’s once-dominant team fails to reverse its slump.

Hamilton’s £40million-a-year contract with the Silver Arrows expires at the end of the season and his future is under the microscope following their poor start to 2023.

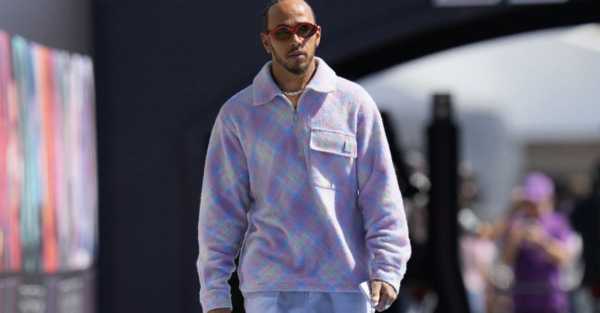

Hamilton was only fifth at the first round in Bahrain before he finished a distant sixth in opening practice on Friday for this weekend’s Saudi Arabian Grand Prix, 1.2 seconds adrift of Red Bull’s Max Verstappen.

Although team principal Wolff remains convinced that Hamilton, 38, will pen a new deal, he also said that his star driver’s head could be turned as he pursues a record eighth world championship.

“If Lewis wants to win another championship he needs to make sure he has the car,” said Wolff.

Advertisement

“And if we cannot demonstrate that we are able to give him a car in the next couple of years then he will need to look everywhere.

“I don’t think he is doing it at this stage, but I will have no complaints if that happens in a year or two.”

Red Bull could have a vacancy at the end of the year with Sergio Perez operating on a 12-month deal, but it seems improbable that Hamilton would be paired alongside Verstappen.

Ferrari is a possible avenue to explore if Charles Leclerc elects to engineer a move away.

But Wolff added: “I am absolutely confident [Hamilton will stay]. We are talking when we want to do it, and how, but we just need to change some terms and the dates basically.

“Lewis is at the stage of his career where we trust each other, we have formed a great bond and we have no reason to doubt each other even though is a difficult spell.

“It will be so nice when we come out of the valley of tears and return to solid performances.”

Advertisement

In Bahrain, Hamilton accused Mercedes of ignoring him on the development of this season’s machine.

Here, the British driver, who on Friday announced a sudden split from his long-time ally and performance coach Angela Cullen, said “we all need a kick” and revealed “there are times when you are not in agreement with certain team members”.

“There are emotions at play with him, with me and with many others in the team,” said Wolff.

“We wear our hearts on our sleeves and sometimes you say things that are translated in a controversial or polarising way which inside the team never causes waves.

“If I am watching a race that doesn’t go well I would also say, ‘I am not happy how the car has been developed’. That is okay.

Sport Max Verstappen shakes off stomach bug to dominate… Read More

“We want the emotions to be high and we want tough love and nobody is not going to take that on the chin in the team.”

Verstappen’s arrival in Jeddah was delayed by 24 hours with a stomach bug, but the double world champion returned from his sick bed to set the fastest time in the day’s opening running.

He finished half-a-second clear of Sergio Perez in the other Red Bull, with Fernando Alonso third for Aston Martin seven tenths back. Hamilton’s team-mate George Russell finished fifth.

X

Sourse: breakingnews.ie