A Chinese scientist has reported he’s created the world’s first gene-edited babies, an announcement that’s shocked the scientific community because it defies an unofficial international moratorium on editing human embryos intended for a pregnancy.

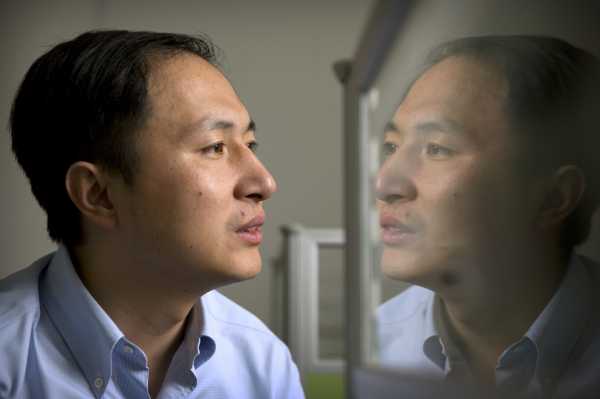

He Jiankui, a professor at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, is claiming to have used the revolutionary gene editing technology CRISPR to tweak the DNA of human embryos during in-vitro fertilization, resulting in the birth of twin girls several weeks ago. The objective, He said, was to remove a gene called CCR5 to make the girls resistant to potential infection with HIV/AIDS.

If the experiment’s results are confirmed by independent scientists, He would be the first scientist known to use CRISPR to edit human embryos resulting in a live birth. (Chinese scientists were also the first to edit nonviable human embryos, which cannot lead to a birth.)

He’s experiment, first reported by the MIT Technology Review and the AP on Sunday, has not been published in a scientific journal and the data have not been peer-reviewed. He shared his findings with the media on Monday just before the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong, and would not reveal the names of the parents or babies involved.

Harvard University’s George Church told Stat that he’s seen He’s raw data and that the claims were “probably accurate.”

But Southern University of Science and Technology — where He has been on unpaid leave since February — said it wasn’t aware of the research, which seems to have occurred off campus.

“He’s conduct in utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 to edit human embryos has seriously violated academic ethics and codes of conduct,” the university said in a statement. “The University will call for international experts to form an independent committee to investigate this incident, and to release the results to the public.”

Other researchers told the AP the experiment was “unconscionable” and “premature.” Feng Zhang, a member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and the co-inventor of CRISPR/Cas9, called for a moratorium on gene-edited babies. Jennifer Doudna, a CRISPR co-inventor from the University of California Berkeley, said in a statement that “this work reinforces the urgent need to confine the use of gene editing in human embryos to settings where a clear unmet medical need exists, and where no other medical approach is a viable option, as recommended by the National Academy of Sciences.”

Church, however, defended the approach, calling HIV “a major and growing public health threat.”

He’s experiment, if confirmed, would indeed be a major scientific advance. But it also creates plenty of tensions and questions; it’s a major breach of the global scientific consensus that CRISPR isn’t yet safe and precise enough to be used in human embryos that result in live births. Let’s unpack the controversy.

Researchers were calling for a “take it slow” approach on CRISPR in humans

The last several years in science have unleashed the CRISPR revolution. CRISPR-Cas9 — or CRISPR, as it’s known — is a tool that allows researchers to control which genes get expressed in plants, animals, and even humans; the ability to delete undesirable traits and, potentially, add desirable traits with more precision than ever before. (You can read about how CRISPR works here.)

Even more fantastically, it’s at least theoretically possible to use CRISPR to hack the human species — to modify the genome to create resistance to — or completely eliminate — chronic or infectious diseases.

But just because we may have the power to do something doesn’t mean we should. And talking about what scientists should do with CRISPR was the point of the international summit at the National Academy of Sciences in 2015. There, scientists from around the world met to discuss how society should proceed with this technology.

In a consensus statement, they drew the line at clinical research that involves editing the human “germline” — or the DNA of sperm, eggs, and embryos that could be inherited by future generations. Although the academy acknowledged that such research had the potential to eradicate terrible genetic diseases or “enhanc[e] human capabilities,” they also said the science was just too new to do so safely or successfully.

A 2017 NAS report on gene editing also stated that clinical trials could be greenlit in the future “for serious conditions under stringent oversight.” But that “genome editing for enhancement should not be allowed at this time.”

There are real limits to what CRISPR can do, at least right now. Scientists have recently learned that the approach to gene editing can inadvertently wipe out and rearrange large swaths of DNA in ways that may imperil human health. That follows recent studies showing that CRISPR-edited cells can inadvertently trigger cancer.

So scientists have generally advocated for a slow, cautious approach to gene-editing human embryos — which makes the news from China all the more shocking. It’s not clear, however, whether He’s technique was actually effective. As the AP noted, “Several scientists reviewed materials that He provided to the AP and said tests so far are insufficient to say the editing worked or to rule out harm.”

He defended his decision this way: “I feel a strong responsibility that it’s not just to make a first, but also make it an example.” Whether others follow his lead, he added: “Society will decide what to do next.”

Sourse: vox.com