The social media history of the man accused of killing 11 people at a synagogue in Pittsburgh on Saturday was littered with anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and rants about Jews.

Many of these posts were on Gab — a social media networking site created as the “free speech” alternative to Twitter, and where the shooter’s profile read “jews are the children of satan.”

Gab is now defending itself as having the mission “to defend free expression and individual liberty online for all people.” But it also bragged on the site that on Saturday it received 1 million hits per hour.

Since its founding, Gab has become an epicenter of extremely anti-Semitic and anti-black content, and conspiracy theories. By welcoming social media users banned from other platforms for violating their terms of service — like the right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos, banned from Twitter for targeted harassment — and using little to no moderation, Gab has become the go-to social networking site for the alt-right and, moreover, the furthest fringes of the far right.

At a time when more mainstream social networking sites have been wracked with questions and complaints about moderating content and ensuring user safety, Gab has taken an entirely different approach: don’t.

The gunman accused of the synagogue shooting was a verified user on Gab, meaning that he showed the site a verified form of identification when he signed up for its services. The site’s reaction so far shows little indication that hosting a man who would go on to be accused of one of the worst acts of anti-Semitic violence in modern American history will change Gab’s approach.

In fact, the site won’t be backing down at all. In an email to me, the site’s founder said:

How Gab works

In August 2016, Gab was created in a reaction to what its founder and CEO, Andrew Torba, saw as mass censorship by social media platforms, generally against right-leaning social media users who were banned for harassing behavior or using racist epithets or anti-Semitic memes, a move some of those banned viewed as curtailing their free speech rights.

Instead, Gab operates without any overarching moderation by the platform itself. Rather, posts are “upvoted” or “downvoted” by users; downvoting a post enough could reduce its reach. (However, the site removed the “downvote” button in the spring of 2017 because it was allegedly being overused.) Users also have the ability to mute other users and certain key words (including racial slurs). As the site’s community guidelines put it:

In an interview with BuzzFeed News in December 2017, Torba said, “What makes the entirely left-leaning Big Social monopoly qualified to tell us what is ‘news’ and what is ‘trending’ and to define what ‘harassment’ means? It didn’t feel right to me, and I wanted to change it, and give people something that would be fair and just.”

Only threats of terror, direct threats of violence, child pornography, pornography, and doxxing are banned from Gab. Paul Nehlen, a white nationalist who ran for Paul Ryan’s House seat in Wisconsin, was banned from the site in April for revealing the real identity of a notorious racist and anti-Semitic Twitter troll (who turned out to be a 28-year-old financial consultant). But in general, getting banned from Gab is virtually unheard of.

And while the site is technically welcome to all, in another interview, this time with Wired magazine in September 2016, Torba said, “People say we’re an alt-right echo chamber. But if there are any centrists, progressives, libertarians, or apolitical people interested in trying something new, I say, please join us.” Torba is an enthusiastic Trump supporter who believes he helped “meme” the president into office; he who was booted from a startup incubator in 2016 for taking part in harassing and threatening behavior.

Gab currently has between 465,000 and 800,000 users, compared to Twitter’s more than 300 million users. That’s because, despite Torba’s purported best efforts, many of the centrist, libertarian, or just plain apolitical people Gab might want to attract already have social media platforms — namely Twitter and Facebook.

But Gab has no problem attracting people whose content wouldn’t be approved on either site for being too racist, too violent, or too extreme; or people whose habit of harassing others on those sites would not be permitted.

That has limited the site’s potential for a wider reach and, potentially, monetization. In 2017, both Google and Apple rejected an app form of Gab because of concerns about hate speech and pornographic materials. Despite, or perhaps because of, all this, users’ allegiance to the site has deepened.

Who uses Gab?

Earlier this year, researchers from the Cyprus University of Technology, the Princeton Center for Theoretical Science, and University College London, among others, published a paper titled “What is Gab? A Bastion of Free Speech or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber?”

The paper found that Gab appeals to right-leaning Americans who support President Donald Trump, and that more “hate words” are used on Gab than on Twitter. (Though not as much hate language as what’s used on the 4chan/pol/site, which has itself become a breeding ground for conspiracy theories):

The authors added:

Because so few users and forms of content are banned from Gab, it’s is a focal site for neo-Nazis and others who want to espouse right-wing forms of anti-Semitism. So alongside rampant Holocaust denial and conspiracy theories, Gab is a place where violent neo-Nazi groups, like Atomwaffen Division (which has been linked to multiple murders), can maintain profiles on the site so that potential recruits can learn more about the organizations. One such posting on the Atomwaffen page reads in part, “give our videos a view, if you haven’t already! HH!” HH is an acronym for “Heil Hitler.”

There’s absolutely nothing subtle about this post: It features a prominent swastika in the center, racial slurs, and the phrase “Join your local Nazis.”

Gab has fought back on Twitter

In response to the shootings on Saturday and concerns about Gab’s relationship with the shooting suspect, the social media site’s Twitter postings have mostly been aimed at showing that Twitter and Facebook are far worse than Gab — arguing that Gab worked with the FBI and pulled down the shooter’s profile almost immediately, and that Twitter permits users like Nation of Islam’s Louis Farrakhan, who has espoused virulent anti-Semitism, to remain on its site.

In that email to me, Torba said, “Gab has spent the past 48 hours proudly working with the DOJ and FBI to bring justice to an alleged terrorist. Because of the data we provided, they now have plenty of evidence for their case. In the midst of this Gab has been no-platformed by essential internet infrastructure providers at every level.”

And to be clear, Twitter does have a major problem with how it handles both harassment and offensive content, which Atlantic journalist Adam Serwer pointed out on the site.

But Gab’s Twitter postings on Saturday were also contentious and aggressive, following a long tradition. They railed against CNN and alleged that BuzzFeed contributors had espoused “anti-white hate.”

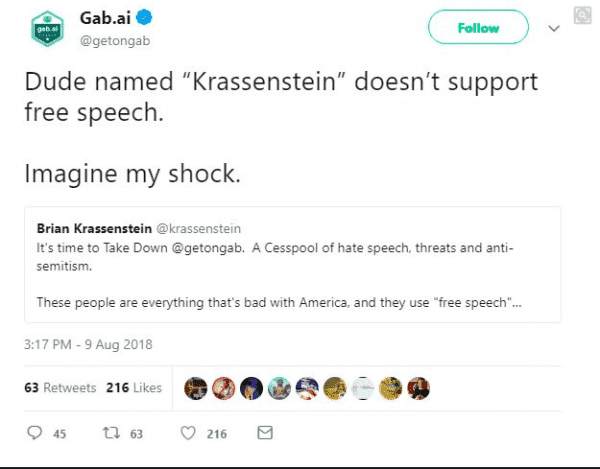

Before the shooting, Gab’s Twitter feed even wielded anti-Semitism as a rhetorical weapon. In August, for example, they argued that someone with a Jewish last name not supporting Gab’s version of “free speech” wasn’t surprising.

By Sunday night, Gab had lost multiple hosting providers, and the site was effectively shut down. On Monday, Gab posted a message on the site that read:

Gab has bet its success on being the social media platform where free speech is paramount and where user experience come in a distant second.

But after becoming the social media epicenter for the anti-Semitic fringes of the far right — including a suspect in some of the worst anti-Semitic violence in this country’s history — Gab’s future is murky at best. And yet Torba, Gab’s founder, remains resolute. In his email to me, he concluded: “No-platform us all you want. Ban us all you want. Smear us all you want. You can’t stop an idea.”

Sourse: vox.com