The first time I saw some street photographs by Garry Winogrand, as a teen-ager in the nineteen-seventies, I was overwhelmed. They were the first photos that struck me as relating to the other modes of creation—modern jazz and New Wave movies—that most excited me then. The probing and insightful new biographical documentary “Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable,” directed by Sasha Waters Freyer (opening September 19th at Film Forum), shows how Winogrand’s confrontational, teeming pictures pulled street photography into artistic modernity. The film puts his work convincingly and revealingly into the context of his turbulent life and the passionate politics of the times. Above all, however, the movie puts on display Winogrand’s singular way of working—and proves that, as with many of the artistic luminaries of the nineteen-sixties and seventies, his process is as original a creation as his art, and is inseparable from it.

Winogrand (who lived from 1928 to 1984) certainly didn’t invent street photography, but he transformed it from an art of observation to an art of participation. As the movie’s copious selection of his pictures shows, he didn’t stand apart from his subjects but among them. His 28-mm. wide-angle lens put him seemingly in the center of the field, surrounded by his subjects and events, not observing or capturing their energy but partaking in it. He found his own outer and inner agitation reflected in that of the world around him, and his images unify him with his field of vision. In this regard, his photographs connect with the films of the leading documentary filmmakers of his generation, such as Robert Drew, Albert and David Maysles, Frederick Wiseman, D. A. Pennebaker, and Richard Leacock.

Bowlero, location unknown, 1968.

Photograph by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand / Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

Like these filmmakers, Winogrand turned his subjects’ presence into a mode of performance; his subjects were participants, and he and they were complicit in the creation of his pictures—at least, to some extent. Unlike documentary filmmakers, who were for the most part immersive among willing, aware, and performative participants, Winogrand was immersive among strangers, who were his involuntary and accidental subjects. He devised an extraordinary technique to create a degree of invisibility, but only a degree of it. One of the revelatory delights of “All Things Are Photographable” is its inclusion of a film clip of Winogrand at work on the street, in which that method is wondrously on display. This precious and extraordinary footage, amplified by discussions with photographers who were longtime friends and associates, emphasizes Winogrand’s singular way of handling a camera and makes clear its decisive effect on his images. Working in a crowd, he brought the Leica to his eye—and dropped it away from his eye—so rapidly that, as the photographer Tod Papageorge says, people didn’t know whether they were being photographed or not, whether he even took the picture. (The photographer and artist Laurie Simmons, discussing Winogrand’s practice, emphasizes the gendered nature of street photography, based on the impossibility, at least then, of a young female photographer not attracting unwanted notice, from catcalling men, while working in city streets.)

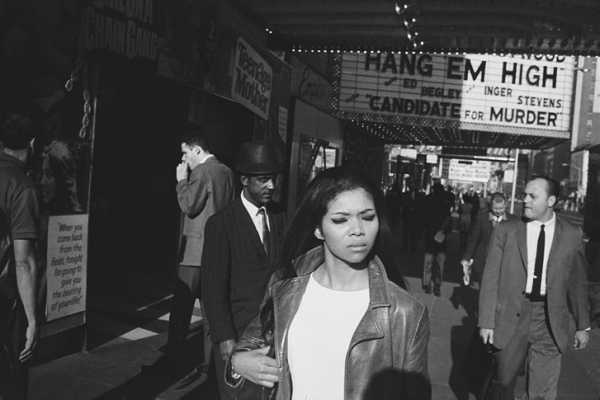

“Hang Em High,” New York, 1968.

Photograph by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand / Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

Winogrand’s contact-averse and conflict-averse strategy was more than a way of getting the pictures, however; it was a built-in aesthetic. It didn’t entirely prevent him from being noticed but, rather, greatly reduced the probability of it. His images often brought together many people unaware of being photographed, caught in a state of public privacy, and only one or two in a crowd who were aware of the camera’s presence and looked into the lens, not so much interacting with him as reacting to him, already too late. He was, in effect, stinging his subjects with the camera, and their gaze back was as an expression of their surprise—a surprise that performed, on camera, his own surprise in the presence of his subjects and the wondrous, shocking, horrifying, astonishing, absurd realities in which he found them.

New York, 1968.

Photograph by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand / Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

Winogrand didn’t take time tweaking and twiddling the camera’s rings and dials, and, above all, he didn’t take time to compose his images. When he flung his Leica to his eye, he didn’t study framing through the lens but composed instantaneously, impulsively, improvisationally, as if he were making a kind of pictorial jazz, or what Jean-Luc Godard called “the definitive by chance.” By means of his process, by means of the invention of a process that’s an inspiration in itself, Winogrand created a body of work that’s also the work of the body. The movie shows how Winogrand created a physical, gestural œuvre in which his presence, his engagement, and his risk were inseparable from and essential to the resulting images. In a 1982 television interview featured in “All Things Are Photographable,” Winogrand talks of avoiding familiar modes of photographic aesthetics; his mode of virtual automatic photography was the technique by which he achieved the aesthetic.

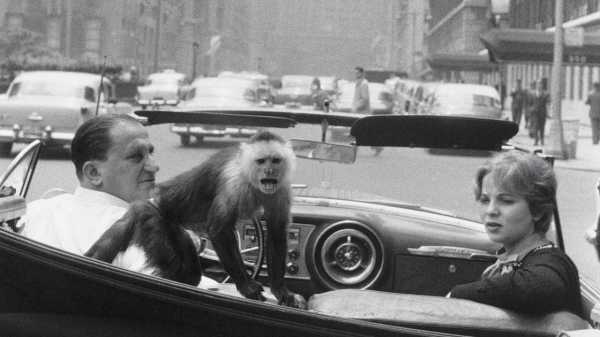

New York, 1961.

Photograph by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand / Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

New York, 1963.

Photograph by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand / Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

But this quality of image also implied quantity: to get his definitive images, Winogrand shot vast numbers of them—an estimated million or more images in his lifetime of work. What he revealed in them was more than the life of his times; he displayed himself in them, too, sometimes in brazenly unpleasant ways, as in his 1975 book “Women Are Beautiful,” which, in an audio clip included in the film, he thinks of subtitling “The Observations of a Male Chauvinist Pig,” and which sparked controversy at the time and, in the film, inspires trenchant discussions with the historians Shelley Rice and Erin O’Toole. In his later years, what Winogrand saw—of the world and perhaps of himself—became hard for him to look at. He left four thousand of his rolls of film processed (i.e., as negatives) but not printed, and another twenty-five hundred altogether undeveloped—thus, he died without ever seeing a quarter-million of his images, nearly a quarter of his life’s work.

Protest, date unknown.

Photograph by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand / Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

Like Orson Welles, Winogrand was a poet of profuse creative incompletion. Something of an exuberant pessimist, Winogrand knew that most of his work was a “failure”; “most everything I do doesn’t quite make it,” he said. He knew that he would salvage few images from the maelstrom of his furious activity, yet toward the end of his life he kept at it even more wildly than before. Winogrand was also, like Welles, a figure of pathos, solitude, and overwhelming humor. In the film, Winogrand and his friends attest that he loved puns, so it’s apt to say that the first posthumous retrospective, held at MOMA in 1988, which included the unseen work of his last years, demanded on the part of its curators a grand Winnowing—a job that, like the recent completion of Welles’s final fiction film, “The Other Side of the Wind,” both fills in artistic mysteries and inevitably generates new ones.

Los Angeles, 1964.

Photograph by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand / Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

Sourse: newyorker.com