Richard Sackler is part of the family that owns Purdue Pharma, the company that is widely blamed for helping cause the opioid epidemic through its marketing of the opioid painkiller OxyContin. But now Sackler, who was previously the president of Purdue, is poised to profit from one of the solutions to the crisis.

According to the Financial Times and STAT, Sackler is listed as one of six inventors on the patent for a new formulation of buprenorphine, a highly effective medication for treating opioid addiction. Buprenorphine is already available as a pill and film, but the new version would be a wafer that may dissolve even faster. The hope is that this will make it harder for people in, say, prison to smuggle buprenorphine when they take it in a clinical setting, since it will quickly dissolve in their mouths. (Since it’s an opioid, buprenorphine can be diverted for misuse.)

That could make the wafer a new, promising treatment in some settings.

But as Andrew Joseph at STAT noted, Sackler’s involvement in the patent has drawn criticism because “the patent could enable Sackler to benefit financially from the addiction crisis that his family’s company is accused of fueling.”

The opioid epidemic began in the 1990s, when pharmaceutical marketing and lobbying led doctors to prescribe far more opioid painkillers — leading to a first wave of overdose deaths as more people, including both patients and people who stole or bought painkillers from patients, misused the drugs and got addicted.

Over time, the opioid epidemic has changed, becoming more about heroin and, most recently, illicit fentanyls (a class of synthetic opioids) than painkillers. But the root of the crisis lies in painkillers; as recently as 2015, most people in treatment for opioid addiction started on opioid painkillers like OxyContin, according to a study in Addictive Behaviors.

Purdue played a key role in that initial cause. Several public health experts explained the recent history of opioid marketing in the Annual Review of Public Health, detailing Purdue Pharma’s involvement after it put OxyContin on the market in the mid-1990s:

By encouraging greater use of opioids for all sorts of pain, the company helped the pills proliferate. They ended up not just in patients’ hands, but in the hands of teens rummaging through their parents’ medicine cabinets, friends and family members of patients, and a black market where excess pills could be sold for a big markup.

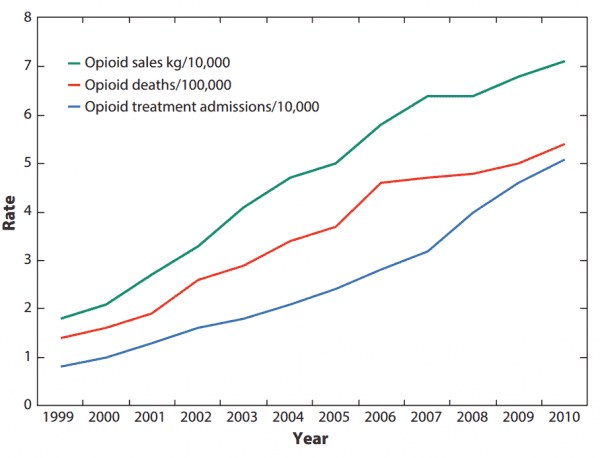

But this was good for opioid makers’ bottom line. As drug overdose deaths and addiction treatment admissions rose, so too did opioid companies’ profits.

Purdue and some of its leaders did pay at one point for the company’s role in the opioid crisis. In 2007, Purdue Pharma and three of its top executives paid more than $630 million in federal fines for their misleading marketing. The three executives were also criminally convicted, each sentenced to three years of probation and 400 hours of community service.

But the fines amounted to very little of the tens of billions of dollars in revenue that the company has reaped from OxyContin since its debut in the mid-1990s and even after 2007. That’s one reason why Purdue still faces hundreds of lawsuits, including from governments, over its marketing of the opioid — although Purdue, for its part, has denied the allegations in court.

Buprenorphine, along with methadone and naltrexone, is one of the medications accepted as the gold standard of treatment for opioid addiction. Studies show the medications cut the mortality rate among opioid addiction patients by half or more and keep people in treatment better than other approaches. When France relaxed restrictions on doctors prescribing buprenorphine in response to its own opioid crisis in 1995, the number of people in treatment rose and overdose deaths fell by 79 percent over the following four years.

Sackler’s involvement doesn’t change the fact that buprenorphine is an effective medication for opioid addiction. But for some people, the potential circumstances of the new buprenorphine version’s release now feel a bit wrong.

Sourse: vox.com