Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In April, Milo Mosquera led the photographer Camila Falquez and her team through the woods near Cali, Colombia, where he lives. By a bend in the Pance River he removed his shirt and walked into the water, Falquez wading close behind. Shoulder-deep, he turned to meet her lens.

In the resulting portrait, Mosquera appears like a carefully sculpted bust with a piece of red silk fastened on his head; his expression is not quite sad, but enigmatic, dignified, almost defiant—though a viewer may wonder whether the twin droplets on his cheeks are tears. “They’re water from the river,” Falquez told me. She was pleased with the arresting quality of the shot. A portrait, she believes, should stop viewers in their tracks, leaving them with questions the image cannot answer. Who is this person? What is their life like?

Milo Mosquera Rodriguez, he/him, Mosquera, Nariño.

Mosquera is one of seventy trans and nonbinary people Falquez photographed for “Compañerx,” a collection of portraits that accompany a legislative proposal to enshrine the rights of genderqueer people in Colombia. In recent years, a coalition of activists and organizations, including the Liga de Salud Trans, has been locating and surveying trans people in every region of the country to get a sense of their struggles and aspirations. When Falquez contacted the Liga about a possible collaboration, in 2022, she learned that the coalition was planning to draw on the survey to draft a bill for Colombia’s legislature which would, among other things, facilitate a process for modifying one’s name and gender on government documents, attempt to combat bias in the health-care sector, and grant preferential housing loans to “vulnerable people of diverse gender identities.” Falquez thought perhaps she could photograph some of the survey participants, whose lives it stood to affect.

Renata Jank Vivas Antonelli, she/her, Cali.

Sófocles Echeverri Soto, they/them, Bogotá.

The bill, Ley Integral Trans, may face a long and contentious path, but it has now been introduced in Colombia’s Congress. “For the first time as an artist, I’m not just left with the manifestation of impossible scenarios, hoping they somehow inspire change,” Falquez told me, describing her excitement about the project. It’s possible that her involvement strengthened the bill’s standing. The language of legislation is often dry and repetitive; it can turn vulnerable individuals into faceless abstractions, their struggles and ambitions collapsed into jargon. In Falquez’s portraits, however, life saturates each frame. Together, the photographs display the kaleidoscopic nature of gender identity, giving flesh and narrative to the different forms it can embody.

Bicky Bohorquez Bisset, she/her, Palmira.

Luz Didian, she/her, Santuario, Risaralda.

Verónica, she/her, Santuario, Risaralda.

Kimberly Moreno, she/her, Quibdó.

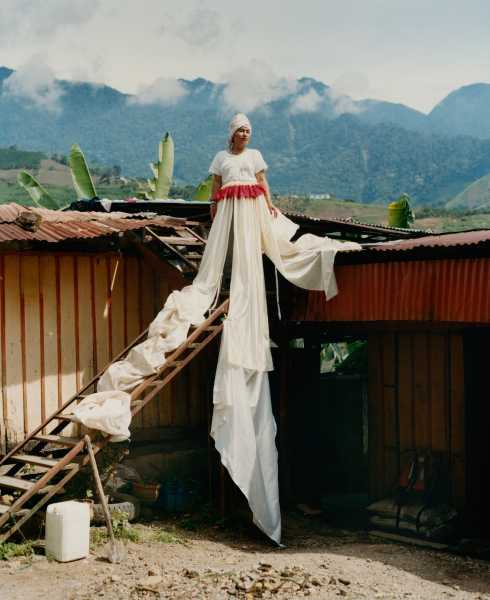

Some of Falquez’s subjects are seen engaged in their everyday lives, standing in the streets of their neighborhoods or sitting next to produce at the market. Others pose in more elaborate settings, devised by Falquez and the stylist Lorena Maza, a frequent collaborator. (The team travelled with a third member, the writer César Vallejo V., who interviewed each subject.) One photo, taken on a coffee plantation in Santuario, Risaralda, shows a woman named Samantha Siagama on a precarious-looking building, her presence so ethereal she may as well be levitating. Falquez asked the woman to climb the structure; Maza fashioned a white skirt from old curtains and coffee sacks found onsite. In the photograph, they cascade down a staircase as if they were echoes of the clouds above. It makes for a mythical image: earth and firmament, something soft and malleable resting lightly over rusted metal.

Samantha Siagama, she/her, Santurario, Risaralda.

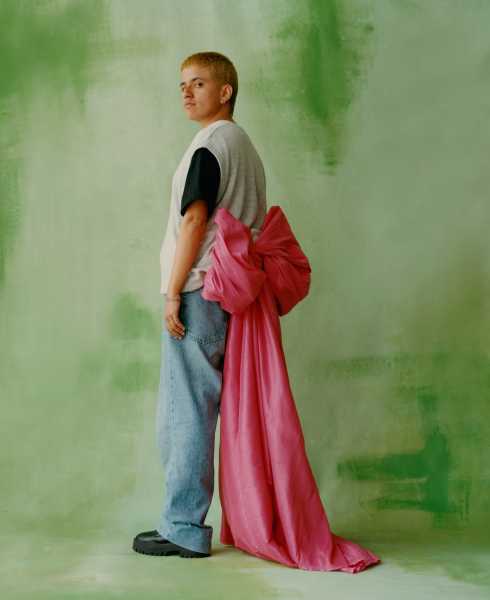

In every portrait, Falquez said, she attempted to depict both the beauty she saw in her subjects and the difficult, often tragic realities they face. The homicide rate for queer people in Colombia, for example, is reportedly the second-highest in Latin America. Falquez and Maza worked simply, carrying only the cameras and a bag of silks in various colors. The silks became a leitmotif of the series. Sometimes, they are draped nonchalantly over a thigh, shoulder, or background; at other times, they envelop statuesque bodies that recall sirens or chrysalides. With varying degrees of fantasy, the photographs convey a singular message: their subjects, who may once have felt broken, appear reassembled, beautiful and ineradicable, their gazes fixed firmly forward.

Alondra Yajaira Márquez Carabalí, she/her, Cali.

Farith Palacios Ortiz, she/her, Quibdó.

Dahianna Beltran aka Barbie, she/her, Cali.

Yosuar A. Mendoza M., they/them, Quibdó.

In one of the most moving shots in the series, Yoko Ruiz, a sex worker and trans activist, stands outside the shop of a man who makes tombstones. “Yoko travelled with us, and she had so many stories of deaths, of members of her chosen family who have been killed,” Vallejo told me. In Ruiz’s portrait, she cradles a blue bundle of silk in her arms, a symbol of the maternal role she’s taken on in her community and its implacable will to survive.

Yoko Ruiz, she/her, Bogotá.

Sourse: newyorker.com