The Met’s exhibit “African American Portraits: Photographs from the 1940s and 1950s,” on view through October 8th, is defined by a double anonymity. Most of the hundred and fifty portraits that compose the show feature unknown sitters, captured by unknown commercial photographers. The museum’s photo curators rescued these portraits from their respective oblivions, and now place them in the canon of American portraiture. They speculate that the majority of the subjects shown in the photos would be in their eighties or nineties now. A note greets the viewer upon entrance: If you recognize a subject, will you assist the team in identifying them, and inform the museum of their fates?

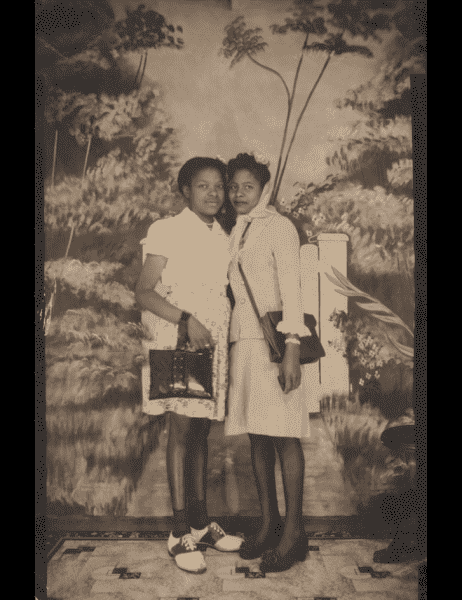

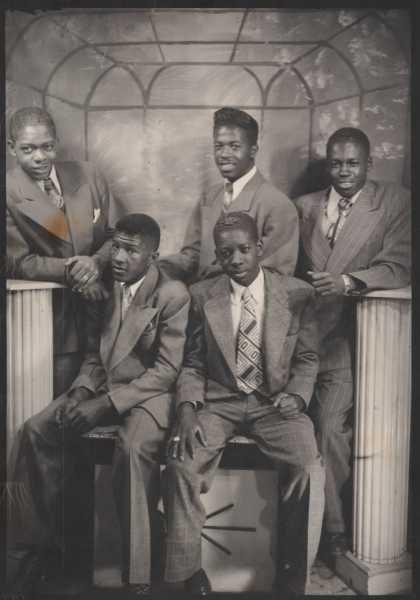

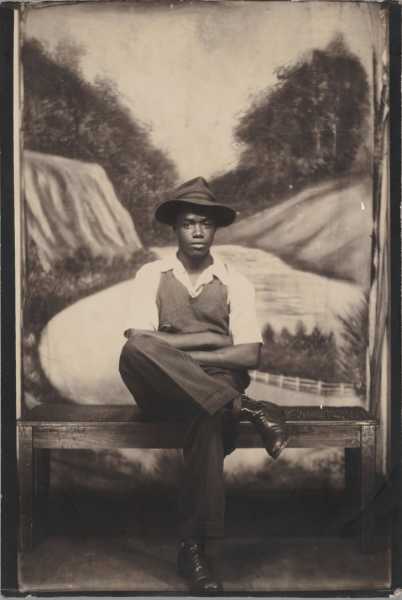

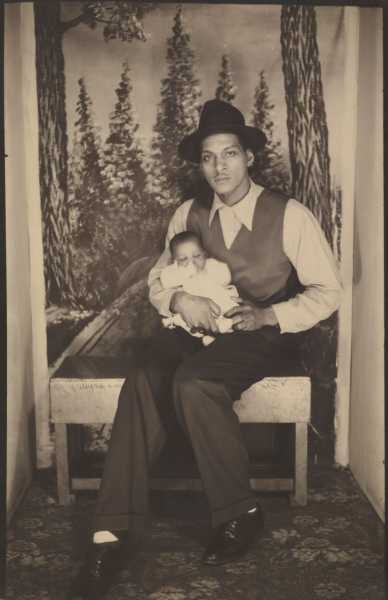

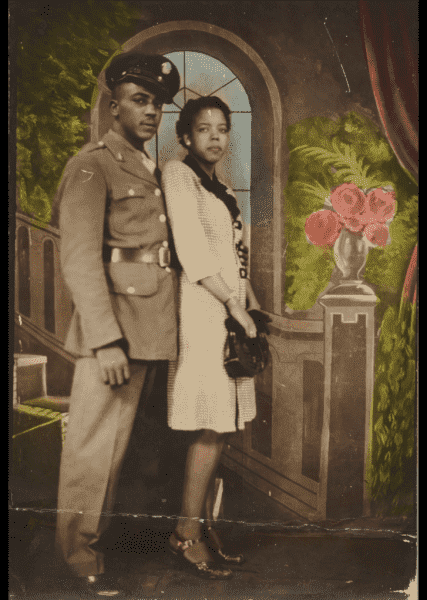

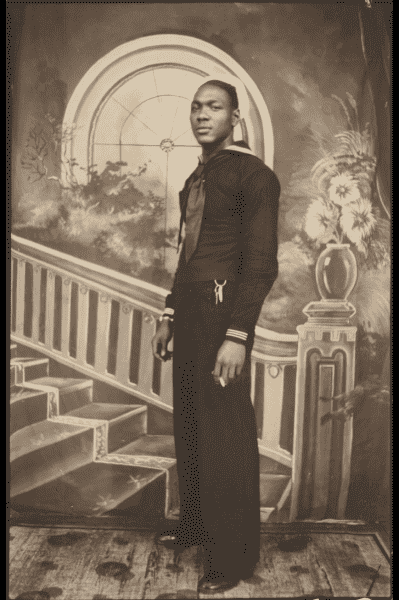

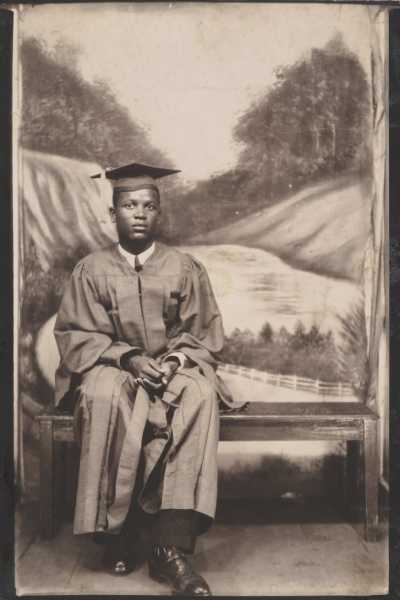

The prints document the aspirations of an incipient black middle class. There are no signs of the ravages of the Great Depression, or Jim Crow, or the Great Migration shadowing these black citizens. Instead, they have outfitted themselves in the trappings of mid-century, middle-class contentment, posed with backdrops of nature or domestic exteriors unfurled behind them. A micro-boom of studios, in part facilitated by innovations that led to cheaper and faster image processing, democratized access to portraitists in the mid-century. (The show’s curators have been able to identify work from two black studios: Daisy Studio, on the historic Beale Street, in Memphis, and R. H. Hick’s Studio, in Georgia.) Sometimes called street cameras, the portable P.D.Q. model (Photography Done Quickly) could produce pocket-sized photographs directly onto paper, forgoing the need for negatives. These stylish sitters needed not wait longer than a few minutes to receive their likenesses. A crowd of five young men in boxy, double-breasted suits are framed by two pillars, in one portrait; the couples—and there are many—burrow into each other. A healthy baby giggles as its mother extends a nurturing hand, the two framed by a background of country bliss; a handsome couple, newly married, are joined in front of a reproduction of a front porch.

Studio Portrait, R. H. Hick’s Studio in Georgia, 1940s-50s

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

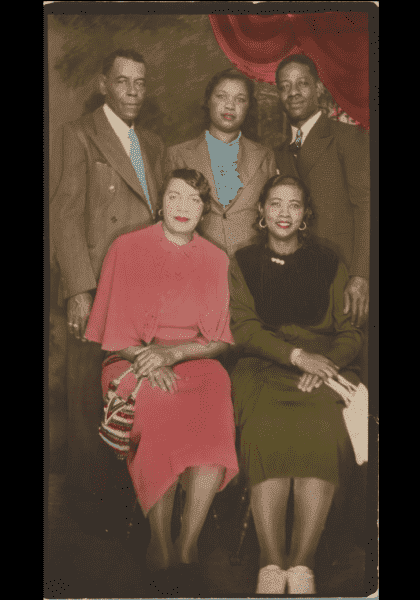

But an eeriness haunts this quaint communal picture. There is the depthless artificiality of the stock backdrops, meant to signal the plenitude of the American land, which make the sitters seem as if they have been dropped in a placeless limbo. Some subjects have evidently requested that their photographs be painted with color—to increase vibrancy, to make them seem more alive—but the tinting has the opposite effect, giving their forms a spectral cast. The direct-positive printing process works by producing a mirror image of the scene the camera captures, which sometimes yields little accidents of translation. Look closely, and find that, in the newlyweds' s photograph, the rings grace the right hands rather than the left; marital order is humorously profaned, and the promise of the new and pristine nuclear black family is thrown quietly off kilter.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

The New Yorker Recommends:

Our staff and contributors share their cultural enthusiasms.

So many of these portraits project fortitude and stability, and yet they were commissioned in a time of roiling industry, of geographical displacement, and of war. Sporadic dating on some portraits of black soldiers indicates that they likely survived conflict abroad, and that their lovers and family likely received similar portraits as proof. But we cannot know if they survived America when they returned. We cannot know whether we are looking at ghosts.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

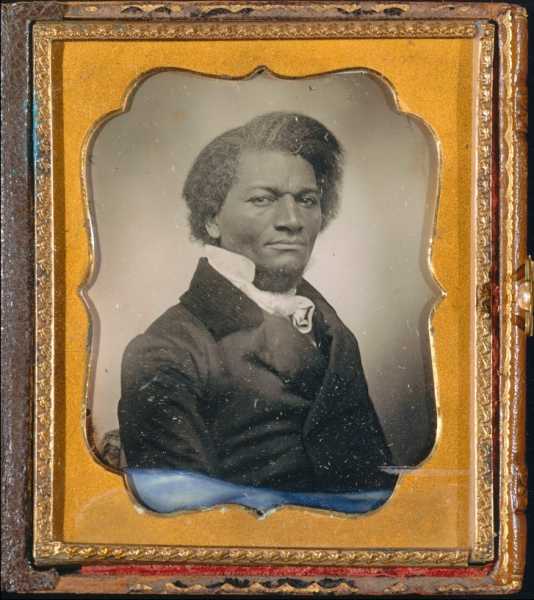

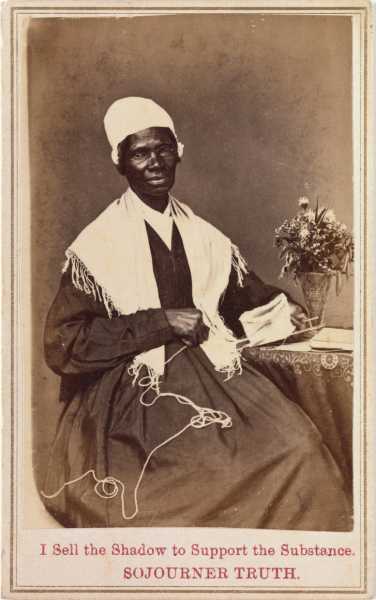

An altering occurs when an institution places relics of real and recent life behind glass, making them into art objects. The portraits in the Met’s show now fulfill the purpose of expanding the museum’s black-portraiture holdings, which are disappointingly small. The images are corralled into common memory, a process that risks degrading the subjects’ vital and specific personhood. Only two of the figures depicted in this small show are widely recognizable, and they are two of the most recognizable subjects in the history of American portraiture: Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. Their portraits are preludes, meant to elevate, and anchor, the exhibit’s mass of unknown faces. But their presence only interferes with the show’s desired coherence. Just as they had differing beliefs on God, the two had contrasting philosophies of photography. Douglass believed that the medium could produce a morally true image of the black subject that harmonized with, rather than diminished, his observation of himself and his freedom. Sojourner Truth was attuned to some other frequencies. She copyrighted her image, and disseminated cartes de visite, which helped pay for her oratorical tours. She allowed her image to be collected, but she did not see it as a vessel of the self. The inscriptions on her cartes de visite read, “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”

Frederick Douglass, circa 1855.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Studio portrait, 1940s–50s.

Sojourner Truth, 1864.

Sourse: newyorker.com