2018 has been a banner year for women in politics. A record number of women are running for office and winning their contests, putting women on track to potentially hold public office in record numbers in 2019. But in the private sector, it’s a different story: The number of women at the helm of the biggest companies in America is on the decline.

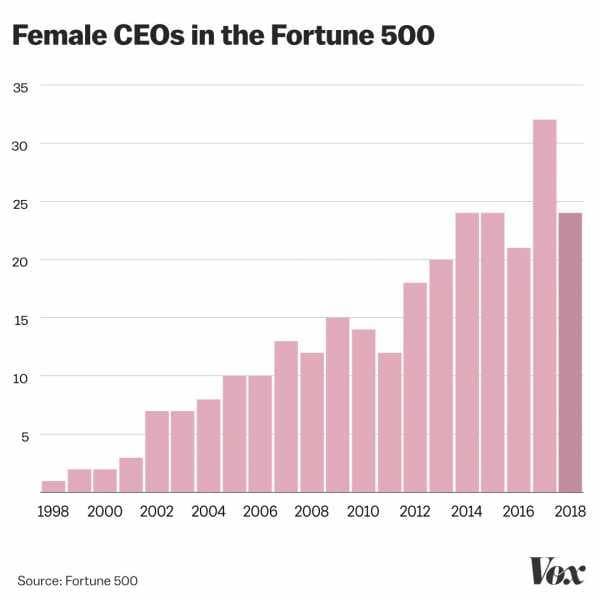

The number of women CEOs at Fortune 500 companies fell by 25 percent this year, dipping to 24 from 32 in 2017, its all-time high. Women are the chief executives of just 4.8 percent of the 500 most profitable companies in the United States.

Women in business and women in politics face similar structural obstacles to gaining power: Historically, they haven’t been valued as leaders, and the systems that propel people in those fields to important positions usually end up keeping men at the top.

But in politics right now, the tide is turning quickly. Fueled by Donald Trump’s victory and inspired by movements such as #MeToo, Time’s Up, and the Women’s March, women are becoming increasingly active in politics and running for office at record rates. Hundreds of women have filed to run for the House of Representatives, Senate, governorships, and other offices, and thousands more have expressed interest in running later down the line.

Meanwhile, in business, you can’t simply sign up to try to be a CEO, the way you can as a candidate for office. The obstacles to climbing the ladder are arguably even bigger. Still, the line you often hear is that women will get there eventually. Sooner or later, parity at the top will just happen — even if it’s decades from now. The Government Accountability Office in 2016 estimated that women would reach parity in the boardroom within 40 years.

For many of today’s working women, that means when they’re retired or dead. And this year’s Fortune 500 numbers on the CEO level indicate that even a glacial pace of advancement isn’t guaranteed.

The big difference between politics and corporate America

The barriers for women in business and politics are very similar. The infrastructure to accelerate women’s leadership hasn’t historically existed. To a large extent, it still doesn’t.

But women have more self-determination in politics than they do in corporate America. A woman can run for office without some higher power sanctioning her ability to do so; a woman in business has to depend on a board of directors to let her in the door and entrenched corporations to help move her up the ranks.

That doesn’t mean the path ahead is easy. It is difficult for women to win in politics, especially without establishment backing. And for women of color, it’s even harder: Axios’s Alexi McCammond reported last week that of the at least 43 Democratic black women running as challengers for US House seats in the 2018 midterms, just one is being backed by the party’s national campaign organization.

“There are women who are told, ‘I’m going to give you a promotion next time,’” said Nevada state Sen. Pat Spearman, who is running to represent Nevada’s Fourth District in the House. “Why does she have to be next, why can’t she be now?’

Still, there are ways of overcoming the obstacles — by running as an insurgent, getting support from outside groups that exist to support women and black candidates, and so on — that don’t necessarily have analogues in the corporate world.

“What you have as a vehicle in politics is you can run against the party machine, you can run without the party endorsement,” said Erin Vilardi, founder and CEO of Vote Run Lead, a group that trains women to run for office.

Take, for example, Amy McGrath, a veteran who won Kentucky’s Sixth District primary in May without the backing of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee.

“Women are individually raising their hands and saying that they want to run for office. That’s a choice that one woman can make,” said Alexandra De Luca, press secretary at Emily’s List, which works to elect Democratic women who support abortion rights.

And in 2018, women are raising their hands more than ever. Emily’s List says it’s heard from more than 36,000 women since Trump’s election who are interested in running for office in 2018 and beyond. (For comparison, 920 women reached out to the organization during the 2016 campaign.)

Vote Run Lead says in this election cycle it’s working to train 12,000 women, and She Should Run, an organization dedicated to increasing the number of women in public leadership, says it’s had more than 22,000 new women join its community in the past year and a half.

Women running for office can jump into the race on their own and test their appeal with voters. Women who want to run a company have no choice but to play the inside game.

“There are a lot of different backgrounds you can come from and get into politics,” said Juliana Menasce Horowitz, the associate director of research at Pew, who has studied barriers for women in business and politics. “With business, it’s a specific background and career trajectory.”

Having women in power is good for business

Having more women in positions of power isn’t just good for women — it’s also good for business. A Peterson Institute study found that having women on corporate boards and in the C-suite may contribute to firm performance and that among profitable companies, a move from no women leaders to 30 percent representation was associated with a 15 percent jump in profit.

Credit Suisse estimates that companies with more gender diversity in the boardroom see better stock market returns and valuations, and McKinsey found that the most gender-diverse companies are 15 percent more likely to outperform their peers.

Elaine Luria, a former Navy commander who is running for the House of Representatives in Virginia’s Second District, told me that her business experience — she owns a family business, the Mermaid Factory — is part of what inspired her to run. She got involved in the legislative process at a local level in pushing for her business and other local art studios to have the ability to serve beer and alcohol.

She also knows the importance of women in leadership: “I’ve seen the difference when you have more women at a military command and in an organization,” she said.

But at the biggest companies, the research hasn’t led to a surge of corporations choosing women as leaders. The high-water mark for women in CEO jobs came in 2017 — at 6.4 percent.

Many women never get to the point where becoming a CEO as a possibility. “There’s a myth that if we just give it time, we will see parity,” said Brande Stellings, senior vice president at Catalyst, a nonprofit focused on promoting women in business.

Women generally start out in the same spot as men in terms of jobs and pay and then, at advanced levels, drop off. According to an annual study from Lean In and McKinsey on 222 companies, women hold 48 percent of entry-level positions. By the time you reach the top executives known as the C-suite, women hold just 21 percent of jobs, and just 3 percent of jobs are held by women of color.

The reasons for this attrition are complex. “There’s a very strongly held perception that the explanation for this, as opposed to an explanation, is work-life balance and family issues,” Stellings said. “It’s really important, but there are many things that go into it.”

Both men and women tend to leave organizations at about the same rate, according to the Lean In/McKinsey study, and very few report plans to leave the workforce to focus on family. But women do bear more caretaking responsibilities. Meanwhile, when men ask colleagues to cover for them, take clients that don’t require them to travel, or make other adjustments to make balancing work and family easier, they often hide those accommodations so they don’t appear to be prioritizing business less.

Cindy Axne, the Democratic candidate to represent Iowa’s Third District in Congress, holds an MBA, runs a small business, and spent a decade working for the state. She said in both the private and public sector, there’s a sense that women have to prove themselves — but there is also often a sense in business that women might be overstepping boundaries in trying to get things done, especially if it entailed clashes with their male bosses.

“As women, there is an expectation that we need to make sure that we follow protocol and ensure that we’re respectful of those who are in supervisory positions in business,” she said. “It’s not so much the opportunity to go and work with the people you know can help work on problems together.”

Boards are overwhelmingly white and male, and they pick leaders who look like them

By the time women want to become CEOs, they need not just a track record but allies who will vouch for them and the support of the board of directors — the majority of which are mostly, if not all, male.

According to Catalyst, women make up about 20 percent of S&P 500 board seats. There are 12 Fortune 500 companies with no women on their boards whatsoever, including Energy Transfer Equity, Icahn Enterprises, and Navistar International. Boards composed of older white men have a Rolodex that looks like them and therefore often don’t look beyond their immediate options when they need to pick a new chief executive.

“If you look at the CEO position as the expression of all the decisions that are made along the way, then the fact that we’re slipping backward is not encouraging,” Stelling said. “The numbers are so small that every single one is notable and scrutinized.”

Janice Ellig, CEO of the executive search firm Ellig Group, noted that there are steps women can take: If a woman wants the corner office, she needs to say so internally and make her name known externally. Women often are slower to call back recruiters than men are, and that can make a difference. And, of course, women need to be prepared for the jobs they want.

“Women have some work to do,” Ellig said. “But the board has to hold their CEO accountable for what he or she is doing to build a pipeline of talent.”

The decline in women Fortune 500 CEOs is “disappointing,” Ellig said, but also a wake-up call for corporations. “The board should be saying, ‘Mr. and Ms. CEO, who’s in line to take your place, what are you doing to prepare them, and do you have a diverse slate?’” she said.

But working on the pipeline of women in leadership positions means change comes about more slowly than in politics, where a single election cycle can make all the difference. In politics, “Unlike at Fortune 500 companies, boardrooms filled with old white men don’t decide elections,” De Luca, from Emily’s List, said. “Voters do.”

Sourse: vox.com