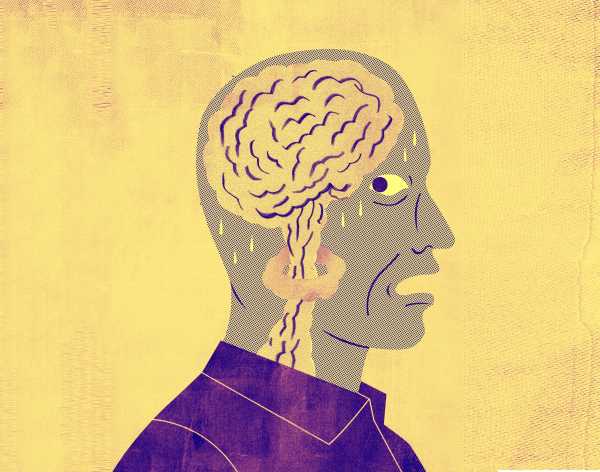

As much as we might tell ourselves our experience of the world is the truth, our reality will always be an interpretation. Light enters our eyes, sound waves enter our ears, chemicals waft into our noses, and it’s up to our brains to make a guess about what it all is.

And I think that’s why the viral audio clip of a robot some people hear saying “Yanny” and other people hear saying “Laurel” is so provocative. Perceptual tricks like this (“the dress” is another recent one) reveal that our perceptions are not the absolute truth; that the physical phenomena of the universe are indifferent to whether our feeble sensory organs can perceive them correctly. We’re just guessing. Yet these phenomena leave us indignant: How could it be that our perception of the world isn’t the only one?

As many have now explained, whether you hear “Yanny” or “Laurel” hinges on whether you’re attending to lower or higher frequencies of sound. Delete the higher frequencies and “Laurel” becomes more pronounced. Do the same with the lower frequencies and “Yanny” emerges.

Hearing one or the other in any given moment ultimately depends on a whole host of factors: the quality of the speakers you’re using, your hearing sensitivities, whether you have hearing loss, the audio-processing regions of your brain, and your expectations, as Dana Boebinger, who studies the neural basis of auditory perception, explained on Twitter.

Many optical and other sensory illusions stem from the same principle: There’s enough information for our brains to make multiple conclusions, but our biases are such that once we choose an interpretation, it can be hard to shake.

After “the dress” destroyed the internet with a debate over whether it was blue and black or white and gold (it is most certainly black and blue), cognitive scientists tried to suss out why the photo caused such different reactions. Twenty-three(!) scientific papers later, the British Psychological Society explains, ”there are no tests available that would allow even the best experts in the land to predict whether you will see the dress as black and blue or white and gold.” It’s still a mystery why there are such stark differences in how people perceive the pattern of colors.

But here’s what one experiment found: Once a person made a judgment about the color of the dress, it was very difficult to make them see anything else.

The “Yanny” versus “Laurel” and dress debates are silly. But their lessons run deep: Our interpretations of reality are often arbitrary, but we’re stubborn about them nonetheless.

And this is a lesson that haunts most of human experience.

For every sense, and every component of human judgment, there are illusions and ambiguities we interpret arbitrarily.

Some of them are fun, like determining whether tennis balls are yellow or green (green!).

Others are gravely serious. Many white people perceive black men to be bigger, taller, and more muscular (and therefore more threatening) than they really are. That’s racial bias — but it’s also a socially constructed illusion.

Our memories are often just a best-guess interpretation of what we lived through as well. We can misremember whole events that never happened. Yet our minds are such that we just assume whatever we remember is the truth of what happened.

Even physical pain is often a misinterpretation. Studies on the placebo effect show that the physical experiences of our bodies can often be changed depending on our expectations.

This isn’t to say you can never trust reality. Often, we’re correct and we agree on it! Otherwise, we wouldn’t have gotten this far. But if someone comes to a different perception of reality, know that their brain may be processing it just a little bit differently.

Sourse: vox.com